The workplace is often where accent bias becomes most visible.

Not because people are openly hostile — but because expectations are tightly enforced, and language is treated as a measure of professionalism.

For many people, speaking with an accent at work means navigating credibility before competence.

Accents Are Not Communication Problems

An accent does not prevent someone from doing their job.

It does not indicate:

- Lack of intelligence

- Poor training

- Inability to lead

Yet in professional settings, accents are often framed as obstacles to effectiveness.

This framing shifts responsibility away from systems and onto individuals — asking them to adapt rather than asking workplaces to listen.

The Myth of the “Professional” Voice

Many workplaces claim to value diversity.

But they often uphold a narrow definition of what professionalism sounds like.

The “professional voice” is typically:

- Accentless or familiar

- Calm but assertive

- Aligned with dominant cultural norms

Anyone who falls outside that standard is quietly encouraged to adjust.

This is not neutrality.

It is preference dressed as policy.

How Accent Bias Shows Up at Work

Accent bias in the workplace rarely announces itself.

It appears through:

- Feedback about tone rather than content

- Advice to slow down or soften speech

- Being interrupted more often

- Being overlooked for leadership roles

These patterns add up — even when no single moment feels overtly discriminatory.

When Feedback Isn’t Really About Performance

Employees with accents often receive feedback framed as helpful.

“You might want to work on how you sound.”

“Clients respond better to a certain tone.”

“It’s just about communication.”

But when the same feedback is consistently given to people with non-dominant accents — and not others — it reveals a deeper issue.

The issue isn’t clarity.

It’s comfort.

The Emotional Labor of Speaking at Work

Speaking with an accent at work often requires extra effort.

People rehearse before meetings.

They monitor pronunciation in real time.

They weigh whether to speak up at all.

This constant self-regulation is exhausting — and largely invisible to those who don’t have to do it.

It’s emotional labor that rarely gets acknowledged.

Leadership and Accent Bias

Accent bias becomes especially apparent in leadership contexts.

Accents that fall outside the dominant norm are often seen as:

- Less authoritative

- Less confident

- Less suitable for decision-making roles

This limits who is seen as “leadership material” — regardless of actual ability or experience.

Why Adaptation Is Often the Only Option

In many workplaces, the path of least resistance is adaptation.

People change how they speak not because they want to — but because they understand the consequences of not doing so.

This creates a system where:

- Difference is tolerated, not embraced

- Success depends on conformity

- Authenticity is treated as risk

What Inclusive Workplaces Would Do Differently

An inclusive workplace does not ask employees to erase their accents.

It:

- Evaluates ideas over delivery

- Separates clarity from conformity

- Trains managers to recognize bias

- Values communication as shared responsibility

Inclusion is not about sounding the same.

It’s about being heard fairly.

Why This Conversation Matters

Speaking with an accent at work should not require justification.

Accents reflect life experience — not ability.

Until workplaces stop equating professionalism with sameness, accent bias will continue to shape opportunity quietly but powerfully.

Because the problem was never how people speak.

It was what workplaces chose to value.

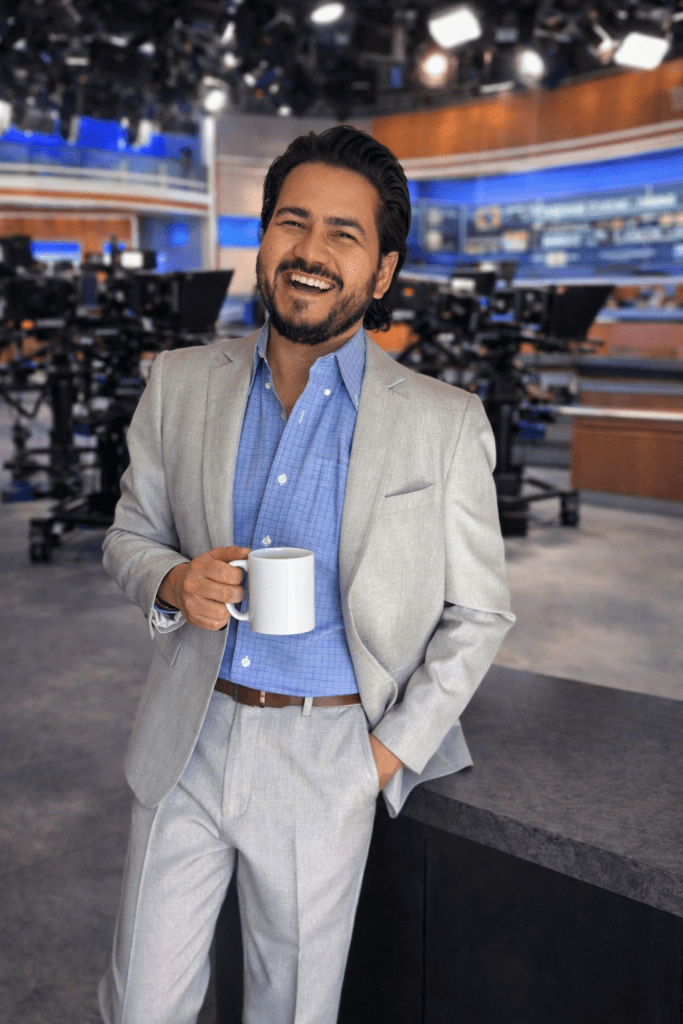

About the Author

José Martínez is a journalist and author who writes about language, identity, and belonging. He is the author of Your English Is Great, But…, a book exploring accent bias, bilingual identity, and the hidden meaning behind everyday compliments.

👉 Your English Is Great, But… is available now on Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/Your-English-Great-But-Languages/dp/B0FHBJKJ6R

Discover more from José Martínez

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.